My first Spartan Death Race

(yes, there will be a second)

In 2025, I finally took on the ultimate test of grit and endurance: the Spartan Death Race.

Friends and fellow racers keep asking me: “How was it?” “Did you finish?” “What makes you want to do that to yourself?”

Rather than repeating fragments of the story, I decided to write it all down — for them, for the organizers and volunteers I owe so much to, and for myself.

Before the Death Race: Arriving Without Wanting to Finish

I registered for the 2025 Spartan Death Race without the goal of finishing it. That’s not something I say lightly. It was clear to me from the beginning. I wasn’t coming for the skull. I wasn’t coming to tick a box. I came to confront myself. To observe. To grow in unfamiliar terrain.

There was also a practical side to it. I couldn’t do everything. Just ten days before the event, I had completed a forty-hour Endurance Trifecta. And one week after the Death Race, I was already committed to a Hurricane Heat 4H. On paper, it seemed minor. But for me, it carried weight — it was a requirement to validate the Spartan Endurance France 2025 finisher trophy. A goal I had already achieved the year before, and, to this day, one I’m the only person in a position to complete two years in a row.

That was the context. I didn’t come to Pittsfield with a mindset of “now or never.” Quite the opposite. I knew that if I pushed too far here — into exhaustion, or worse, into injury — I risked losing everything I had built the rest of the season around.

And I have to be honest: traveling to the Death Race from the other side of the world isn’t something you do casually. There’s logistics to manage, jet lag to absorb, gear to transport, all the usual unknowns that come with long-haul travel. None of that helps you arrive feeling grounded. I came in fully aware that I might be cut from the race within the first ten hours. And in some way, I had already accepted that possibility.

I wasn’t there as a contender. I wasn’t looking for a podium. I came as a learner, someone curious about what this world really looked like from the inside. I knew the Death Race was its own thing — a space where what we think we know about training, strategy, and endurance gets tested in unfamiliar ways. I wanted to understand that from within.

I had no guarantees. And I think that helped. It left space for something more important than control. During the pre-race interview, they asked the usual question: “Why are you here?”

I didn’t need to think long. My answer came easily.

“I strongly believe that we learn the most in struggle and pain. The Death Race is the ultimate struggle test.”

That was the reason. Not to win. Not to impress. But to experience. To step inside a kind of chaos, and see what it revealed.

During the Death Race: A Gradual Wearing Down

The Death Race doesn’t begin with a whistle. It begins well before that.

From the moment we arrived, the tone was clear. Nothing was clearly marked. We waited without knowing why. There was pressure, but it came without direction. You couldn’t tell if what you were doing was part of the event, a test, or just a way to wear you down slowly. The uncertainty became part of the atmosphere. Doubt settled in early, and it stayed.

By the time the race was declared officially underway we were already inside it. Nothing had changed dramatically. It just kept going. And from those first hours, the rhythm was sharp.

The physical test (PT)

Early on, maybe twelve hours in, we were assigned a physical assessment. A simple list, but heavy in its demand:

- 100 push-ups

- 100 sit-ups

- A one-mile hike with 40 kilograms and 300 meters of elevation

- 50 burpees

- A one-mile farmer’s carry with a five-gallon bucket filled to three-quarters

- Five minutes of wall sit with a 25-kilo sandbag in the arms (not on thighs)

There was a timer, but no explanation. We didn’t know why we were being timed, or whether the result mattered. But in the Death Race, anything that seems meaningless often returns later, reframed as essential. I thought there could be a time cutoff, eliminating the slowest ones. So I gave it nearly all in an effort to pass.

When the PT ended, the race didn’t pause. It just kept moving. Time dissolved into daylight, cold, night, and mud. One layer after another. And somewhere within all of that, a task was assigned — 550 tire flips, using a tire weighing close to 170 kilograms. There was no assigned session. No one watching with a clipboard. You were expected to fit them in as you went, and someone from the staff needed to validate it by punching a card. A few before another task. A few more while waiting. They added up, or didn’t. Either way, they were always there — never truly done, just paused for later. A thread woven into the race from beginning to end.

The Cold Water

One of the moments that stands out very early on in the event was the water. There was a pond, not far from where we gathered. The temperature hovered around four degrees. We entered it once. Then again. And again. It was clear something more was coming, even if no one said it out loud. Eventually, we were grouped together — thirty-eight of us. We were told we’d be doing thirty-eight full-body immersions. One per participant. Each one had to be done in perfect synchronization. If someone went under too early or too late, the group would start over.

The water took your breath every time. Your body tensed. The shock didn’t wear off, only deepened. It became harder to breathe, harder to think, harder to come back up and remember where you were. But we kept going. Once. Again. Again. This was where the nature of the race became clearer. It wasn’t about brute performance. It was about slow dismantling — not a collapse, but erosion. A test not of how much you could do, but how long you could stay present inside something senseless.

The Tunnel, the River, the Poem

Hours later, a new task was given. We had to rush to a cabin we had visited a few times already by then, and we should know the way. The last 4 people would be cut off. I did my best, and arrived second. I got assigned a number. I took my pack, the same I had carried since the beginning — about forty kilos — and was pointed toward a tunnel.

It was narrow. You had to slide or crawl through it on your hands and knees. Once through, you stepped into a shallow river. Water at your feet. Then you dropped down again, crawling under barbed wire. Slowly. Carefully. Until you reached a tree laying down. There, a laminated poem was tied to the trunk, printed upside down. You had to memorize the stanza that matched your number.

Then you returned, still with all of your gear. Back through the river. Back through the tunnel. And once you reached the top, you recited the stanza. If it wasn’t perfect, you started again. If you passed... well, you got assigned a new number, and you do it again anyway.

This cycle lasted for around 10 hours. The same process. Memorize. Crawl. Recite. Restart. People gave up. Not because they were injured. But because the task no longer seemed to have a point. It was long. It was wet. It was cold. And it didn’t move the race forward in any obvious way.

I stayed with it. I took breaks. I sat when I needed. I didn’t try to gain time — only to stay in motion, gently, one step at a time.

The Sauna

At another moment, we were told to build a sauna. Not use one. Build it ourselves. Once it was done, we stepped inside. The temperature rose quickly. First sixty degrees, then eighty. We stayed in for over an hour. Inside, the challenge wasn’t just the heat. We were told to get our phones that needed to be readily charged. The task: write a one-thousand-word essay on the theme “YOU MUST.” Later on, we'd need to email it. You'll find the result just below...

Time passed strangely. Writing became slow and unclear. The heat made focus difficult. At some point, burpees were added. No explanation given. The body could hold out. But the mind began to slip. That was the actual challenge. The heat was secondary. The real test came from the absurdity of the situation, and from what it asked of you quietly: to keep going when the task no longer seemed to make sense. It wore people down. Not all at once, but gradually. Which, again, was the point.

You Must

Written by Nicolas Fiorini, in a Sauna, for an unknown duration 🤣

It was a rather ordinary winter in 2024. I was walking home after a night out with friends. I took my usual route — the shortest one. As I stepped out of their home, I felt something strange. A presence, heavy and still, as if I was being watched. I told myself I was imagining things. I had been drinking, after all, and my mind was foggy.

But the feeling didn’t go away. At the third turn, the shadow became real. I realized my senses weren’t dull at all — they were sharp. A man was following me. That, in itself, wasn’t so unusual. As a young woman, attention like that is sadly familiar. But this wasn’t just a passing glance. He was following me, unmistakably.

I changed direction. Looped around. Nothing worked. He kept closing in. I tried to speed up, but so did he. My heart was pounding. What did he want?

He eventually grabbed my wrists. In that moment, everything retreated into my mind. I would never hurt someone — so where were his limits? My thoughts froze. Fear took over. For about five minutes, I let myself shut down, completely overwhelmed by emotion.

And then, something shifted. My awareness came back.

This man was clearly stronger than me. I had a gas spray on me, just for situations like this. I knew exactly where it was. But then came the impossible choice — was it safer to pull it out and use it, or to let things play out and hope for the best?

That’s when I heard it. A whisper: you must. It grew louder. You must. Until it became a scream: YOU MUST!

I reached for the spray and aimed it at his eyes. His reaction was immediate — he pulled back, yelling, swearing. But it was enough. I ran. Straight to the subway. No way I’d let someone like him know where I lived.

Since that night, two things have stayed with me. First, of course, the fear. The image of what could have happened if I hadn’t acted. But also that voice. That instinct, deep and fierce and clear. Something primal. Something I didn’t know was in me. I’m not someone who usually acts on impulse. But in that moment, it felt like the only truth.

And that voice didn’t disappear. I’ve heard it again — in moments of doubt, when important things are at stake. Where fear once filled the space, now I hear that quiet certainty. You must enter this competition. You must speak up at work. You must tell your mother you love her.

The reason doesn’t always matter. What matters is that doubt no longer gets the last word.

As brutal as that experience was, it taught me something I carry every day. I became stronger — not just in how I relate to men, but in how I approach life. I don’t thank my attacker. Of course not. But I do thank myself. For choosing to act. For deciding not to let that moment define me in silence. That growth is mine alone.

And I share what I’ve learned with my children. They’re still young — ten and eight — too young for the full story. But not too young to understand one simple truth: doing something is better than doing nothing. Taking a chance is what moves things forward. Inaction only preserves the status quo.

They’ve absorbed that idea. I see it in how they face challenges. I tell them often: failure is not trying and failing. Failure is not trying at all. I feel a deep pride when they attempt something, even if they fall short.

My oldest recently missed her newly learned gymnastic moves at a competition. The disappointment didn’t last long. What replaced it was pride — not just mine, but hers. Because what value is there in repeating what everyone else can already do? She had tried something new. She had taken a risk. Just like Simone Biles has done, again and again. That same voice must have lived in her too.

Champions try. Presidents try. Even those struggling deeply try — and in trying, some of them change.

Today, I am a woman who tries. Who trusts herself. Who stands her ground. And I owe that not to some plan or training — but to that single voice that rose from somewhere deep, in the worst moment of all.

So next time you find yourself in a hard situation, listen closely. That voice is there.

You must.

Because whatever the outcome, you’ll know you stood up and gave it everything.

The Final Phase

Around the 56th hour, we were told that the final phase had begun.

Like most things in the Death Race, the term didn’t have a clear definition. We knew there was a cap time, but undisclosed, by which we should have finished this phase, or we wouldn't be finishers. It simply meant that we had reached the last layer — the part that comes after the early filters have done their work. Some had dropped out. Others had been cut. What remained now would determine how it ended.

To be considered a “finisher” in this edition, there were four tasks to complete, in this order:

- Start a strong enough fire, using a firesteel.

- Repeat Thursday night’s PT and beat your previous time.

- Climb Mount Sparta (over 1000 feet of gain), observe a small LEGO construction for thirty seconds, descend, and rebuild it from memory.

- Complete six laps of the farm carrying a yoke — about six miles in total.

All of this, of course, came with a condition: if you hadn’t already completed the 550 tire flips, they needed to be done too.

The Turning Point

It was during the second task — repeating the PT — that things began to shift for me.

The physical demand alone would have been enough after two and a half days of effort. But there were other complications. My bucket was gone. Whether it had been taken or moved didn’t matter much. I reached for someone else’s, assuming I could adapt. He reacted sharply. Accused me. I tried to explain, tried to stay calm. It didn’t help. I handed it back and walked off to refill a new one.

That detour cost me precious time. I missed the target. Which meant I had to start over. Another full round, and this time, the mental weight was heavier. The effort itself took about an hour and forty minutes. Twice. Both times under stress. And in both cases, without food. I’d been so focused on the clock that I forgot to manage my energy. Rookie mistake, one that I had learn to avoid, but 50hrs+ was a new territory for me and I paid this lack of lucidity.

A few hours later, the effects showed up. I slipped into hypoglycemia. My body slowed. My mind scattered. And somewhere in that quiet unraveling, I began to reflect. Not in a dramatic moment, but over time. Piece by piece. Thought by thought. What I felt wasn’t a wall, it was a decision. I hadn’t come here to finish. Not this year. This wasn’t the centerpiece of my season. I had shown up to learn, not to give everything away.

And I understood — slowly, clearly — that continuing would have meant putting everything else at risk. I was not crashing to the point that I wouldn't recover. I could have taken 30 minutes, rest, eat, hydrate properly, and get back to it. But these recent events made me realize how little control I had over the situation. This was new to me, since I had done extremely long events, but never that long. So I realized that while I could continue with a few adjustments, there was risk attached to it, and most likely a price to be paid.

Reaching the Part I Came For

After finally completing the second task, I was tired. More than tired. Worn out, but still present. It had taken a toll. Not just physically, but mentally as well. The pressure of the clock, a tense moment with another participant over a missing bucket, and nearly four hours of poor nutrition had left a mark. Not one large event, but a series of small ones, each adding to the weight of the experience.

Then came the third task. On paper, it seemed simple, at least compared to what had come before. Climb Mount Sparta — one mile, with a thousand feet of elevation — observe a small LEGO structure at the top for thirty seconds, then return and rebuild it exactly as it was.

But, like everything in the Death Race, simplicity fades the moment you step into it. Thirty seconds to memorize a structure in three dimensions — built from maybe 15 pieces — while dehydrated, underfed, and mentally stretched thin, was harder than it sounds. A single mistake — one misplaced block — and the climb began again. Which meant that every second spent observing carried doubt: did I see enough? Did I remember the order?

I made the climb. I looked. I turned the model over in my head, quietly. Then I walked back down. And somewhere in that descent, something shifted. I didn’t stop because I placed a block wrong. I didn’t stop out of frustration or confusion. I stopped before trying. Not as a refusal, not in collapse.

It was more like a recognition — slow, quiet, and sure — that I had already reached the part I came to find. There was nothing more I needed to prove.

After: A Decision, the Lessons, and What Comes Next

I didn’t place the first brick. Not because I was done, not because I had been pulled from the course, and not because I had lost interest. I still had something in reserve. My body wasn’t at its limit — a few blisters, some soreness in the shoulders — nothing unexpected after that much time on course. But what I did have, and what felt rare in that environment, was clarity. I said that I was out of the race. The staff tried to talk me into staying (something they rarely do, quite the opposite!) by asking if I could put a single piece, go look again, improve. I responded that I got it, I wasn't overwhelmed by the task. I knew this was designed so that we'd go up and down 5-10 times until we learn it by heart. But that wasn't an issue for me, really.

It wasn’t a dramatic moment. Just a quiet realization, the kind that settles in gently. I had enough space in my head to ask the real question: do I need to go further? And the answer was no. I hadn’t come here to finish. That was never the plan. The Death Race wasn’t the focus of my season. Ten days earlier, I had completed a forty-hour Endurance Trifecta. In a few more days, I was scheduled to complete a Hurricane Heat 4H — a critical step step to secure a goal I had spent a long time working toward.

The truth is, that event meant more to me. I had already made that choice in the way I structured my year. You don’t place a Death Race 10 days after a 40hr-long grueling event if finishing it is your highest priority. And that honesty helped. It gave context to what I was feeling. I knew that if I kept pushing here — if I ignored where I was and what I needed — I risked losing everything that came next.

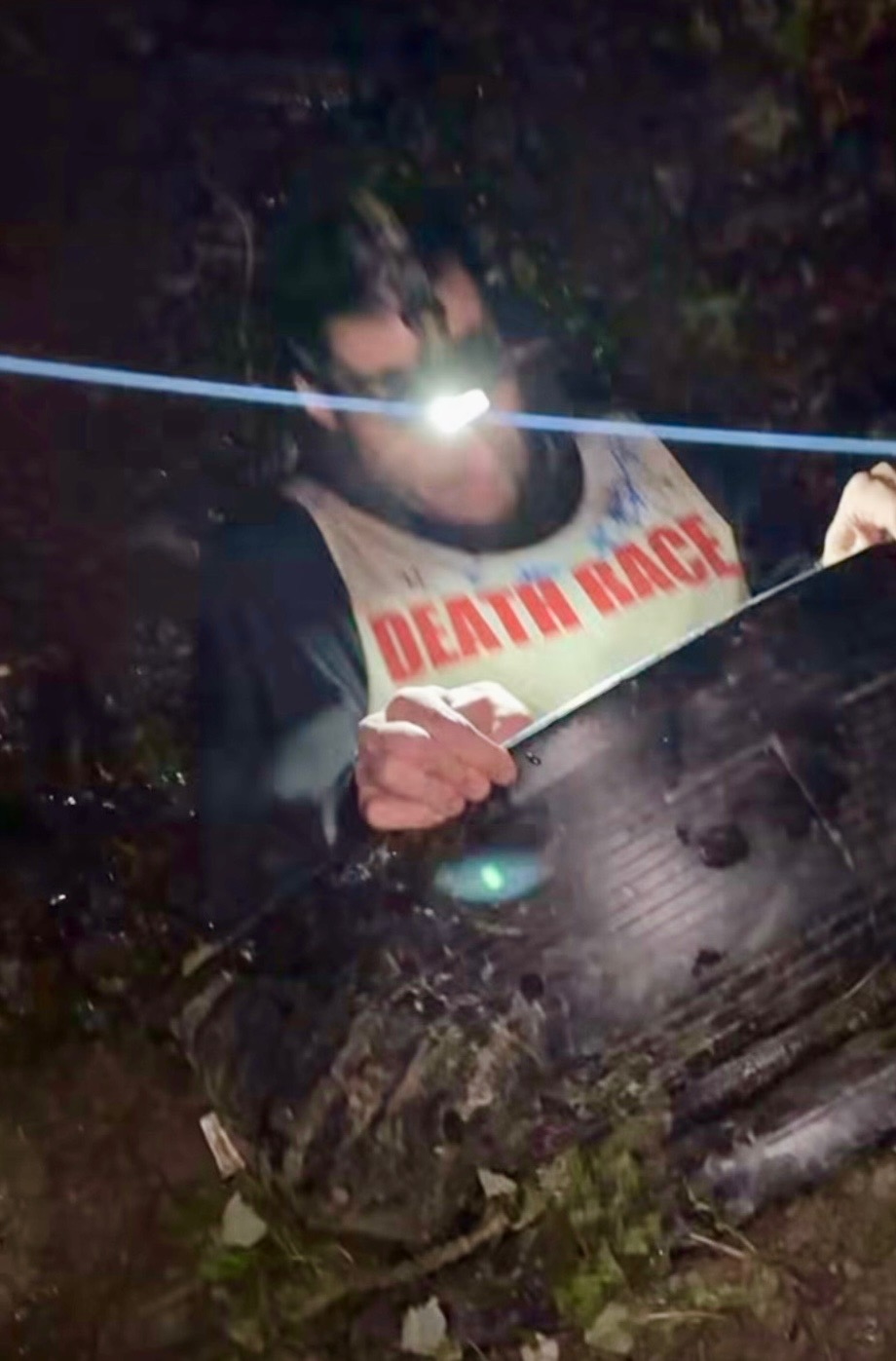

So I stayed with the original intention. To come here to observe. To experience. To learn something about a world I didn’t fully know. And to leave before the purpose was lost. There was no collapse. No pride on the line. No dramatic moment of walking away. Just the quiet sense that I had seen what I came to see, and that was enough. So I gathered my things, and left. And the picture at the top of this article illustrates it quite well, I believe. Or the one just above, taken a few hours before the night I'd quit. Always smile.

What I Learned

There were plenty of tangible takeaways. Too many to be listed here, really. I learned how to manage nutrition more effectively under stress. How to react faster when something goes missing. How to hold clarity in moments of friction. How to recognize when emotion is starting to cloud execution.

But above all, I left with one essential understanding: No one finishes a Death Race by accident. It’s not just about hanging on a little longer. It’s not raw resilience. It’s a matter of alignment — of priorities, choices, timing. Everything has to point in the same direction. Your training. Your mindset. Your sleep. Your recovery. Your calendar.

Finishing isn’t a bonus, it’s a project. And this year, it wasn’t mine. I like to make an analogy with gold medalist at the Olympics. Do you think some of them earn the gold without doing everything they can to get that gold? Absolutely not. Sure, not everyone aiming at it will get it, and we need to remain humble. But to get it, you need to have structured your entire life and made all of the sacrifices to achieve it. Same for the Death Race.

With Thanks

First, the Death Race team.

To Andi, the race director — for her presence, her steadiness, and her clarity amidst so much uncertainty.

To Don — as unpredictable as he is iconic — who appeared at the least expected moments, like a video game boss dropped into real life. His deep “EXCUSE ME!” still rings in my memory.

To those who support me regularly, visibly or behind the scenes:

- Leonidas & Sara (Spartan Endurance France)

- Will (HH staff)

- Laure (massage therapy)

- Aurélie (coaching)

- Anne-Charlotte (osteopathy)

To those whose own paths inspired mine — often more than they realize: Julien, David, Benji, Christian, Pepe. You’ve shown me how far we can go when we don’t lose sight of why we’re going there.

To my mother, who encouraged me to pursue sport even when I was asthmatic — even though I only really listened at age 31.

To my wife, who accepts the daily training, the weekends away, and this strange pursuit of chosen difficulty.

To my children, who cheer me on with a sincerity that disarms me, even when they stumble across photos of the Death Race with “I MAY DIE” written in bold.

And to everyone else I crossed paths with — before, during, or after — thank you. I can’t name you all, but you made a difference.

And Now?

I plan to return next year, but I don’t yet know what my intention will be.

Will I come to finish? Maybe. But if I choose that path, I know what it will require. I’ll have to center everything around it. Step away from other events. Adjust my training. Accept the risk of failure again. And also the strange uncertainty of success — and not knowing what to do with it once it’s in your hands. I've got some experience with it already from when I won the Abalone World Championship. And great success clearly isn't just happiness, it's very complex to manage internally.

Even with that kind of focus, there’s no promise. I could last only five hours. I might not make it into the final phase. That’s part of what this race is — preparation and reality don’t always line up. The race itself is designed so you can't prepare.

So I’m giving it time.

Time to reflect.

Time to let this experience settle into place.

Time to come back to it with the distance it deserves.

And when that moment arrives, I’ll decide how I want to return.

What I do know already, though, is that I will.